The post-World War II geopolitical landscape was complicated. Britain and France moved to flex their muscle during the Suez Crisis, but events made the United States the West’s true leader.

In 1956, the president of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser, nationalized the Suez Canal, which had mostly been owned by British and French investors. This canal was a major part of ocean-going shipping and allowed ships to pass into the Mediterranean from the Red Sea, effectively linking Europe to the Indian Ocean and trade from Asia. Swiftly, Israel, Britain, and France moved to intervene and invaded Egypt. Against the background of the Cold War and the anti-colonialism movement, the aggressive actions by Israel, Britain, and France heightened tensions with the Soviet-backed Arab states in the Middle East. The United States, Soviet Union, and United Nations criticized the intervention.

In 1798, a French general named Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire, with some 30,000 troops. Napoleon’s successful invasion and seizure of Cairo, the capital city, was quickly noticed by the British. With Napoleon’s massive army helpless on land, the British destroyed the French fleet in the Mediterranean. Moving by land, France faced another crippling blow when the British allied with the Ottomans to thwart Napoleon’s plans to take Syria. After just over a year in Egypt, Napoleon returned home to France, where he began seizing power as a dictator.

Though Napoleon and some of his top staff had returned to France, his troops remained in Egypt and occupied the country until 1801, when they evacuated. Strong ties between France and Egypt remained, as Napoleon had brought with him many scholars who eagerly studied contemporary and ancient Egyptian culture. Egyptian culture became extremely popular in France, known as Egyptomania, a phenomenon that eventually also found its way to Britain. During the mid-1800s, as photography and archaeology became popular, France focused heavily on Egypt as a source of inspiration.

British interest in Egypt began in the 1860s due to two events: the US Civil War (1861-65) reducing the amount of cotton exported to Britain from the American South, and the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869. Swiftly, Egypt moved to increase cotton production, which would be bound for the textile mills of England. The Suez Canal also benefited the British, as ships could now pass through the Mediterranean to reach India. At this time, India was Britain’s most valuable colony. This began a political tug-of-war between Britain and France regarding which European power would “control” Egypt.

Between the 1880s and World War I, Britain came to dominate more and more of Egypt’s affairs. Officially, Egypt was under the control of the Ottoman Empire, and the outbreak of hostilities between the Allied Powers (which included Britain) and the Central Powers (which included the Ottoman Empire) allowed Britain to seize control of Egypt. This year, 1914, saw Britain seize the Suez Canal and declare Egypt a protectorate. After World War I, Egyptians began fighting for independence, which was granted in 1922. However, British troops remained in Egypt until 1929, when they withdrew. The Suez Canal zone, similar to the Panama Canal zone in Central America, remained under British military control.

Both Britain and France had historic ties to Egypt, and both were facing strong anti-colonial headwinds after World War II. France, which had been wholly defeated and occupied by Nazi Germany, sought to regain its colonies after the war. This included much of North Africa, particularly Algeria. The British had stationed troops in Egypt to protect against Italy and Germany seizing the Suez Canal. However, the end of the war brought about a swift desire for decolonization. Many people questioned how Britain and France could want to retain their colonial empires after a war had been fought to prevent the empires of Nazi Germany and fascist Japan.

However, Britain and France did seek to retain their empires, at least initially. In Europe during the War, the British units under Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery were allegedly used cautiously to preserve their strength for maintaining an empire, and British, Australian, and Indian units controlled many former colonies in southeast Asia after defeating the Japanese. Quickly, people in southeast Asia began demanding independence. Although Britain decided to grant independence to India, France attempted to hold onto French Indochina. In 1954, the defeat of the French in Vietnam at Dien Bien Phu led to the end of French control in southeast Asia.

The decolonization movement coincided with the rise of the Cold War. The Soviet Union, one of the victorious Allied Powers of World War II, was looking to export communism. It could offer aid to newly independent nations or rebel groups hoping to win independence. This sparked fears in the United States that refusal to decolonize could provide political and military openings to communists. Refusal to decolonize also created public relations problems, as maintaining colonies seemed opposed to the principles of democracy and state sovereignty supported by the US, Britain, and France.

Egypt was of interest to the Soviet Union during this era because of the Suez Canal and its location on the Mediterranean. More generally, the Soviet Union wished to improve relations in the Arab world, and Egypt was considered the most modernized Arab state. In 1955, an arms deal was made between Egypt and the Soviet Union, run through Czechoslovakia. Egypt’s president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, made the deal after approaching the United States for weaponry. When the US did not offer a desirable deal, the Soviets jumped at the chance to befriend Egypt as an opportunity to gain a toehold in the Middle East. Israel, the newest nation-state in the region, was firmly allied with the West, making Egypt the desired partner of the USSR.

In July 1952, a coup overthrew king Faruk I of Egypt, and one of the main plotters was a young man named Gamal Abdel Nasser. Three years later, Nasser was Egypt’s undisputed leader and positioned his country as one of the leading nonaligned states, meaning it was neither a formal ally of the United States nor the Soviet Union. However, Nasser was not a true Marxist and focused more on Arab nationalism and decolonization than socialism. On July 26, 1956, he announced the nationalization of the Suez Canal. This violated a 1954 agreement that said the Suez Canal Company would not be transferred to Egyptian control before 1968.

Immediately, diplomats went to work to avoid armed conflict. The United States, despite being staunch World War II allies of Britain and France, did not support the possibility of war in the Middle East. An American proposal was to give 18 of the world’s leading maritime powers and Egypt equal ownership stakes in the canal, but this consortium idea was rejected. Between August and October, Britain and France held secret talks with Israel about a military invasion of Egypt, as Israel considered Egypt a military threat to its sovereignty.

On October 29, 1956, Israel began its invasion of Egypt on the Sinai Peninsula and defeated opposing Egyptian forces. The Israelis advanced toward the Suez Canal from the west using ground forces. This conflict between Israel and Egypt was not shocking, as Egypt had been one of the several Arab states to fight against Israel in the Arab-Israeli War of 1948. The United Nation’s creation of a new Jewish territory in November 1947, using the land of British Palestine, was seen as an encroachment on Arab sovereignty. In May 1948, just as the new nation of Israel declared its independence, war broke out between it and neighboring Arab states.

Israel won its war for independence, but intense hostility lingered. Egypt prevented Israel from using the Suez Canal, motivating Israel to wrest the canal from Egyptian control. As Israeli forces pushed toward the canal in autumn of 1956, a trap was sprung by Britain and France against the Egyptians. Having plotted ahead of time with the Israelis, Britain and France called for a cease-fire by both sides in the growing war. When Nasser rejected this cease-fire, as was anticipated, Britain and France had an excuse to engage militarily.

With Egypt having rejected the cease-fire, British and French bombing of Egyptian targets began on October 31. For a few days, the European powers focused on neutralizing the Egyptian air force, planning to establish control of the skies. On November 5, both Britain and France began landing paratroopers at airfields and ports. An amphibious invasion occurred simultaneously, with Royal Marines coming ashore with tanks and other armor. Some Royal Marines arrived via helicopter, marking a first in warfare.

Supported by armor, the British took the Suez Canal with virtually no opposition. However, Nasser limited the effectiveness of the Europeans seizing the canal by blocking it with sunken ships. Egyptian forces also destroyed some oil production in Iraq, which had been under British domination since World War II. The blockage of the canal and Egyptian attempts to destroy oil bound for Europe threatened to greatly worsen an ongoing oil shortage. Altogether, however, the combined Anglo-French invasion of Egypt had been a swift military success.

Despite their military victory, Britain and France found themselves surprised at a diplomatic firestorm. The United States, led by president Dwight D. Eisenhower, condemned the invasion. The US believed the war would push Arab states into alliances with the Soviet Union, especially if American forces were needed to back up the British and French. Additionally, the US did not want to be seen supporting two aggressive colonial powers in an age of decolonization and also did not want to appear hypocritical after having just condemned the Soviet Union for its intervention in Hungary.

In a surprise move, the United States publicly criticized its two World War II allies in the United Nations. The US also promoted the use of UN peacekeepers, as opposed to troops from allied nations, to secure the canal. Although these moves created tensions between the US and its two European allies, they likely bought much goodwill from Arab states and prevented them from pursuing close alliances with the Soviet Union.

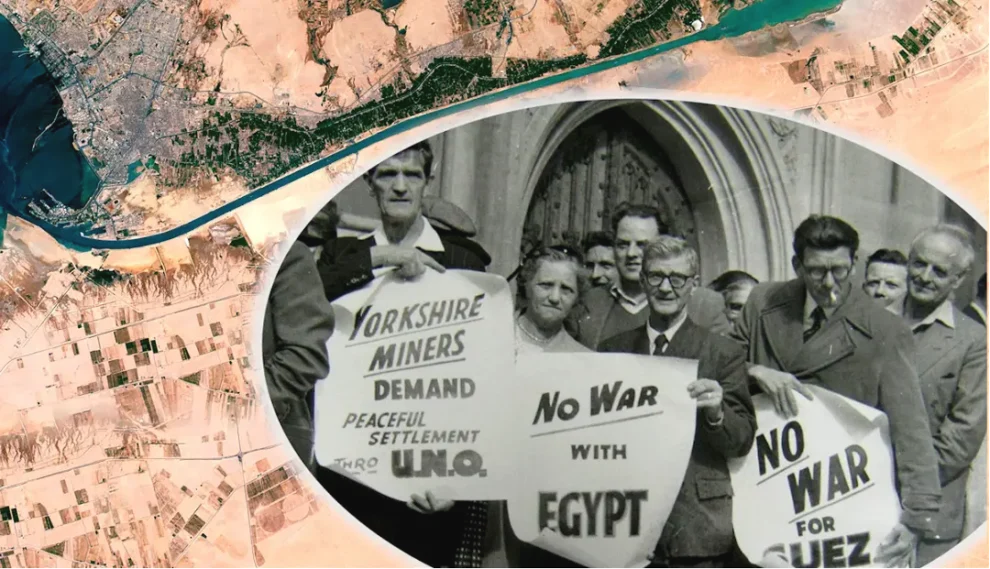

The Anglo-French invasion was criticized not only by the United States but also by the international community and many domestic protestors. Soviet diplomats issued vague threats, such as sending volunteers to assist the Egyptians if Britain, France, and Israel did not agree to a UN-backed cease-fire. Although there was no indication that the Soviet Union planned to engage militarily, the possibility of Soviet volunteers in Egypt coming under fire could risk expanding the war greatly. However, the biggest threat to the Anglo-French alliance in Egypt was financial.

In 1956, the value of the British pound was falling. Faced with oil shortages from the Middle East, Britain needed to buy oil from the United States during the Suez Crisis. Eisenhower refused to sell unless Britain accepted a cease-fire. The US also threatened to sell its holding of British pounds, flooding the foreign exchange market and reducing their value. Faced with a financial crisis, Britain had no choice but to agree to the UN cease-fire. Britain quickly pulled its troops from Egypt, followed soon thereafter by France and Israel. In exchange for having its troops out of Egypt by December 22, Britain was allowed access to a large loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The humiliation of the Anglo-French alliance during the Suez Crisis shifted power dynamics in the West. Britain could no longer count on its “special relationship” with the United States to guarantee unwavering support in foreign affairs. In the era of decolonization, Britain and France were unlikely to find many international allies when trying to impose their will on other countries. The Suez Crisis generated international goodwill for the United States, which played peacemaker instead of joining its historic allies for an easy military victory.

Financially, the Suez Crisis revealed America’s trump card in foreign affairs. Only the United States had enough wealth and economic output to pursue such unilateral military aggression so far from its borders. Britain had been unable to hold onto India, and France had failed to hold onto Indochina. Needing America’s strength to protect from potential Soviet aggression in Europe, Britain and France had little choice but to defer to the US in terms of foreign policy. The Suez Crisis ended the heydays of Britain and France as unilateral world powers.

Source: The Collector